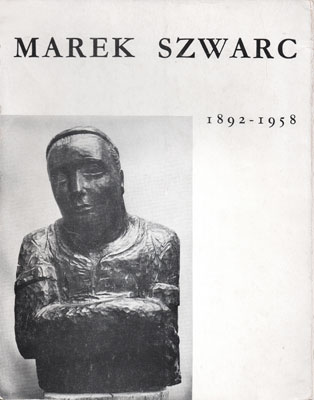

Marek Szwarc

by Meyer Levin

Arriving in Paris as a young man of eighteen years old, during the summer of 1924, I found lodgings in a pension on boulevard Montparnasse, in the heart of the artists’ quarter. I’d published by then a number of short pieces in The Menorah Journal, and I had a letter of introduction to an artist who’d been the subject of an article in the journal. His name was Marek Szwarc. The article in which he appeared was illustrated with photographs of bar reliefs in hammered copper, representing biblical scenes that were striking in their passion and in the purity of their line and beauty of composition. In the midst of the Modernist movements, at the very center of Cubism and of Dadaism, there existed an artist who dared affirm an ancient faith in which the work of art retained its popular features while appearing at the same as modern as the “moderns,” by dint of its singular expressive power and its imagination set free of realistic trappings.

The editor of the journal had in a sense intuited an affinity between the Parisian artist and my own sensibility. But he didn’t have the artist’s address. “Ask around, he told me, you’ll surely find him.”

I had begun to make inquires at the pension when everyone set themselves down at the table for dinner. Sitting next to me was a modest-looking man who seemed cordial and kind. Having told me that he was an artist, I asked him whether by any chance he knew an artist called Marek Szwarc. It was he, Marek Szwarc.

This coincidence marked our friendship with the sign of fate. Szwarc exercised an enormous influence on my life and even, at a later date, he would become my father-in-law. At the time his daughter Tereska, who shared the single room occupied by Marek and Guina, in Mme Content’s pension, was still an infant.

Shortly thereafter I visited Szwarc’s studio and admired his first sculptures; a curious fact, his very first work realized in Paris was an Eve. We were surrounded, in the little atelier, by biblical personages, Abraham, Moses. There were also family portraits from an earlier period when Marek was primarily engaged in painting.

Szwarc became my guide to the galleries, to my choice of reading; he revealed to me not only France and the Arts, but Europe. When I returned to Paris, several years later, I noticed a Deposition executed with the same simple piety as his figures from the Old Testament. That was when I heard that he was Catholic, but it was rather the mystical aspect of his faith that made sense to me and which I formulated not so much in terms of his Catholicism as in Hassidic terms.

The world of Hassidism was completely unknown to me until the day I discovered it by way of the tales of the Baal Shem Tov, which Szwarc loved to recount. When I asked him for the source of these marvelous parables, he handed me a series of little pocketbook pamphlets in Yiddish that he had collected in his native Poland and brought back to Paris. I plunged into the reading of these tales and decided to translate into English a collection of Hassidic tales. The result was The Golden Mountain, for which Marek etched a series of masterful illustrations.

For years I’d arrange to return regularly to Paris and inevitably I would spend most of my time with Marek and his family. I knew of the terrible suffering he had endured over the years, ostracized by the narrow-minded who showed only contempt for his conversion. In spite of this, his art continued to develop constantly and profoundly and his own character retained its natural kindness and unlimited benevolence.

During the war we were fated to meet again in London. Szwarc had been given leave by the Polish army to work on his sculptures; he had, without question, set out on a completely new series of major works, which were to surpass all that he had so far realized. He had become a maître.

After the liberation of Paris, having the good fortune of being the first person to enter the atelier on boulevard Arago, which had been so familiar to me, I was able to write to Marek in London that everything remained, quite miraculously, intact.

During the ensuing bountiful years I was able to follow from up close the genesis of each work of art: I saw the rebirth of the personages of the Old Testament, conceived with a penetration of increasing ardor, the theme of Moses was reprised again and again, the theme of the Sacrifice of Isaac, even as Szwarc drew his subject-matter from the New Testament—such as the archaic and classic Mother and Child—and from secular subjects, for example The Resistance. Everything was original; Marek never relied on a preexisting language and never produced a work which did not proceed from an intimate need to give form to an idea that had emerged from his own interior life.

His daughter and I and our children were living in New York and then in Israel during his last years. Toward the end of 1958 I happened to find myself in Paris while on my way to Israel, and on the eve of my departure I visited Marek in the hospital. He was recovering from an operation and was impatiently anticipating his return home. In several months he and Guina were to pay us a visit in the Holy Land.

We spoke principally of the voyage. Of what it would mean to live for a time in the country from which his entire oeuvre virtually found its origin. We also spoke of his last works set aside in the atelier, realized just before his hospitalization in order to undergo surgery. They were three large sculptures in olive wood and several smaller pieces of lyric character, also carved in olive wood, because, he said, a friend who lived in the French Midi had spoken to him of a number of felled olive trees in his property whose wood he had offered to Szwarc as a gift. Libera Me, his very last work, was a reversed tree trunk, he explained to me smiling, pleased at having succeeded in transforming the roots into arms raised toward the sky.

And certainly this windfall proceeded from what he had made of his life.

The following morning he was no longer of this world.

Meyer Levin

Originally published in the commemorative catalog Marek Szwarc 1892 – 1958. (Paris, 1960.)