Louis Vauxcelles

on Marek Szwarc

(Translated from Artistes Juifs. "Le Triangle” Editions, Paris. 1932)

A pure being, steeled by his faith, prays and works in solitude. Nothing discourages him, neither misery, nor raillery, nor insults. His direct gaze rises and soars. The buzz of vanities that exasperates, the clatter of venomous quarrels, the tumult of interests that tear one another to pieces, have no affect on him. In his solitude, hard by his wife, gentle and courageous, and his ingenuous, little girl, he hammers the metal with a skilled hand, at once strong and delicate. He meditates on the pages of the Book. Between the leaves surge up the immortal figures of Abraham, Jacob and the Angel, the marvelous features of Moses that Claus Sluter and Buonarotti have modeled, which he in his turn sculpts and chisels, and the couple Ruth and Boaz. The artist gazes at them, speaks to them, consults with them; his pencil, then his mallet evokes their pains and their joys; he recreates them, presents them to us, without a care for archaic reconstitution or exegesis. This unique soul is called Marek Szwarc.

*

I have, among the throng of painters, sculptures, French and foreign artisans, native or deracinated, waxing, vegetating or prosperous in Paris, met over the last thirty years many a type – singular, unusual, exceptional: Georges Rouault, mendicant monk of the Middle Ages, soul brother of Léon Bloy and Jacques Maritain, in which the violent, naïve and passionate work cries out in misogynous contempt and hate of a decaying society; Georges Desvallières, this mystical warrior; the statutory Manolo, clever and charming Catalan, who would preserve the gift of childhood in the hovels of Montmartre before evoking, in the Pyrenees countryside of Céret, the Virgilian shepherds; Angel Zarraga, gentle and wise Christian colorist, friend of the elect, gifted with a universal culture; Balgley, engraver and painter, of an exalted and luminous temperament, haughtily puissant, in which resonates the imprecations of the prophets of his race … Have I ever encountered anyone that was comparable to my dear Marek Szwarc?

Whenever, weary of incessant jousts and of the mental strain of the quotidian, I make my way to his atelier, tucked away in a populous neighborhood, hardly have I entered this asylum of work and peace, that a calm descends over me, my nerves relax … we speak only of painting and sculpture; Marek Szwarc knows the young maîtres of today, judges their worth with a discerning and subtle appreciation. But this evangelical heart has a secret and constant ambition to communicate its certitudes to others, wishing to lead us to the beatitude in which he rejoices; in possessing his own truth, he burns to share it with his tormented brothers. He senses God indwelling within him; the celestial presence is everywhere; he touches it with his fingers; God guides his hand, his pencil, his mallet. Marek’s only justification resides in relation to this presence; he collaborates with God. And Marek knows that God alone offers peace to those for whom peace has fled … Alas! Who, of all our contemporaries, is closer to the Angel of Fiesole than this humble Jew? To labor, is to pray. Marek Szwarc’s dream would be, rather than a form of haughty individualism, which is the law of the century, the self-effacement of the anonymous laborer. The spirit of the medieval image-makers relives within him. He is close to the great Christians, the Henry Cochin, the George Desvallières. “Art,” wrote Desvallières, “is one of the means by which Providence grants man to open his heart. The greatest artist is he who unbosoms himself most generously and, in relating to us all his miseries, all his joys, all his hopes, illumines our own. Hence all pure art is fundamentally prayer, and all works of art bear an apostolic force. It is why art, in serving God alone, expresses itself most fully, achieves its greatest perfection.”

And Henry Cochin: “Art bears within itself the power of instruction.” They were well aware of as much, the carpenters and stone masons who, in the fourteenth century, covered Sienna with a coat of frescos; for they did not fear to attribute, as the paramount status of their guild, a sublime function and to call themselves: ‘Revealers of the truth.’”

Unrealizable dream in the twentieth century? Perhaps … but who knows?

During six centuries, in all of Western Europe, the plastic arts were in the service of faith: Memling and Fra Angelico, Morales and Dürer narrate on the walls of churches, of baptisteries, of cemeteries, of communal and manorial palaces, the agony of the Passion, the piety of the saints, the glory of Christian heroes; the dawning images of their hands instructing the people. A fresco had an educational and moral role: it was a homily. In the significant phrase of the Assembly of Prelates, painting was in the service of the Church. “We are, by the grace of God,” the Siennese painters would say, “those who make manifest to gross and illiterate men those miraculous things accomplished by virtue and in the name of the saintly virtue of faith.” And Albert Dürer wrote: “The art of painting is in the service of the Church; its mission is to show Christ’s suffering and other edifying models.” The adoring Christian legend furnishes us with Quattrocento triptychs, the Bourguignon statuary, the stain-glass windows of Chartres.

Might any of this surge back to life? No one believed so.

What might come out of this movement of Catholic idealism? Will they chase the merchants out of the Temple?

Must one answer to such valiant props to a declining faith that a new symbolism has been born, as distant from Greek anthropomorphism which populated Hellas with marble gods, than monastic belief? That a scientific mystique grants a glimpse into a world of new concepts? And that the Benedictine school of Beuron, the pre-Raphaelitism of Holman Hunt and Watts in England, that or own Rose-Croix, have bruised their wings in attempting the impossible resurrection?

*

The “plastic homely” of the revealers of truth, will it once again grant us to hear its persuasive eloquence? This problem of the resurrection of Christian art is beyond us and certainly does not concern us here. If I have sketched it out a propos Marek Szwarc, Jew, it is because there is no contradiction between the concepts of this artisan and those of his Catholic colleagues. None, to the contrary, is in greater agreement with Jacques Maritain than Marek Szwarc; by diverse paths they aspire to the same ends, scaling the same slopes. In the communion of ideals, these pure ones clasp each others hand. We are talking then neither of Catholic nor of Jewish art, but rather of religious art.

Did I say Jewish art? Another question surfaces, irksome, complex, which one must touch upon.

Marek Szwarc’s art, might it be marked (others will say spoiled, adulterated, vitiated, gangrened) by Semitism?

And, first of all, is there specifically a Jewish art in 1930? If it exists, does Marek Szwarc express it? The question, confessional, becomes ethnic.

A Jewish art … It has been said and it has become a topical observation, there is not one painting at the Louvre museum signed by a Jewish name, — apart from two works, recently granted refuge in the sanctuary, by Camille Pissarro, exclusively inspired by realism and a vision of impressionist technique.

Hence, neither painters, nor sculptures nor Jewish ornamentalists at the museum, at least up to our own times. It seems to prove that the sense of color, as of form, are lacking among the nation of the elect.

Here is what appears irrefutable: from the Middle Ages up to our own times, not one Jew in the academies of Italy, of Spain, of Holland or Flanders. The race obeys the biblical verses: “You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

In the nineteenth century a number of assimilated Israelites appear: Max Lieberman, Brandon, Israels, Léon Bakst, but they are still the exception to the rule in the ateliers.

All of a sudden, soon after 1900, and for the most part after the First World War, such an onslaught of locusts, an invasion of Jewish colorists fall upon Paris – upon Paris of Montparnasse. The reason for this exodus: the Russian revolution, and the misery, pogroms, exactions, persecutions, which came in its wake; the unfortunate young artists sought refuge with us, drawn by the shining light of contemporary French art. And hence, alongside our French Jews, from Paris, Nîmes or Alsace (Caro-Delvaille, Adler, Kayser, Léopold or Simon Lévy), disembark the adolescents of Petrograd, Krakow, Berlin, Vienna, Munich. They will constitute one of the constitutive components of what the young critic would call “The School of Paris.” Numerous talents will be considered in this throng of aliens; some of them will even become renowned. And they will be – I can only mention the principle ones: Modigliani, Zak, Pascin, Chagall, Soutine, Balgley, Kars, Kisling, Grünewald, Iser, Feder, Terechcovitch, Milich, Mondzain, Kikoïne, Krémèegne, Czobel, Kramstyck, Mané Katz et Maurice Gotlieb, Samuel Hirschenberg, Altmann, the Americans Maurice Stern and Max Weber, Marcoussis; Mmes Blum, Muter, Lévy-Bloch. Add to these names the painters belonging to the Chareau residence, sculptures and engravers Joseph Hecht, Cavaillon, Kogan, Lipchitz, Zadkine, Nadelman, Loutchansky, Mestchaninoff; Mme Orloff, Indelbaum, etc.

And our Marek Szwarc.

How explain, after the silence of two, of three millenniums, such a bustling? After this absence, this insolvency, such a plethora, such a teeming pullulation?

Ingenious, affronted aestheticians, in need of an explanation, as moralists, have looked into this singular phenomenon. One will claim that since the taste for speculation has come into play we observe Jews flocking toward those professions which have suddenly become lucrative. He will add that this monetary influence will attach itself to, will superimpose itself on another influence, that of the Orient on the Occidental arts; in his eyes the cult of variegation, and of deformation, of the grimace, of ugliness, was of Judeo-oriental importation.

For another, the key to the enigma resides in the inborn facility of assimilation. Jews have devoted themselves to the liberal professions only since their emancipation, recent in history. And, not bringing to the practice of art any distinguishing ethnic mark, their art reflects solely the culture of the country in which they live. The question of education plays here a larger role than the racial component. Pissarro is an Impressionist, another Israelite painter will be a Fauve, a Matissian or a Picassoian. Strictly speaking, there is then no Jewish Art: the influence of the milieu is the only preponderant. Without denying the sensibility and spirit of the Israelite, one must admit that the assimilated Jewish artist may become an excellent artist without being indebted to the Talmud.

What conclusion may be drawn from this collusion of contradictory theories, and above all what may be secured, as to what concerns the artisan whose works – and soul – are the object of this study?

One might be tempted to opt for the assimilation thesis. Jewish Artists, writers – critics –born in Paris, are first and foremost Frenchmen. Granted, they may owe to their origins a certain antenna-like subtlety – but nothing more.

Is Marek Szwarc’s art Jewish, in the sense understood by Mr. Van der Pyl? A taste for deformation, for the imaginary? Yes, perhaps, but the kind of deformation by Marek Szwarc is executed and stressed – as it is understood by all great artists – according to character, and it is a necessary amplification of the volumes; nothing here bespeaks of a specifically Semitic feature: the artist is conforming to eternal laws. Distant successor of Medieval artisans, he applies a rough and vigorous hand, unsullied by wished for naiveties, but moving by virtue of the religious emotion which this mystic feels and desires to communicate. To speak of grimace, of oriental variegation in relation to the severe oeuvres would be a sacrilegious joke. Oriental? So be it, since Szwarc is devoted to the figuration of biblical themes.

But what might these expressions further signify: “Facile art, careerism, thirst for lucre,” etc? They have no currency in the atelier where we observe our friend at work. His disinterest is as pure as his aloofness from the powers that be is profound; he belongs to no coterie, does not frequent any salon, any art review office, any Rotonde. He has vowed himself to poverty and solitude.

Assimilated? No. And it is a rather exceptional case: Marek Szwarc, a Pole of Paris, a Parisian of Lodz, loves, feels, understands, venerates France, the culture and art of France, but he intends to obey the tradition of his ancestors and to remain Jewish at heart, in faith, and in sentiment. If there is in France only one artist and one work of art representing Jewish art in the same way as the poetry of Spire or the prose of Fleg are Jewish literature, I would nominate Marek Szwarc rather than the illuminist Balgley, or Laurence Lévy-Bloch, this Louise Hervieu of Rosiers street. Balgley admires the Bible for its beauty; Szwarc cherishes it for its truth; you will grasp the distance which separates them, which separates this Jewish artist from all his coreligionists. For Marek Szwarc – and what a difference from the hallucinations of Soutine, amorist of disorder – Jewish art is order, which governs the relation of the Creator to the creations. Art is prayer. To fulfill one’s task in pleasing God. And to persuade one’s brothers. Haven’t I told you that this Jew belongs in the company of Henry Cochin, George Desvallières, Jacques Maritain?

Persecutions cannot defeat the man and the artist who is sustained by his faith.

His dream was, I repeat, to be an anonymous artisan, in emulation of the masons who toiled in the courtyard of the cathedral.

*

Examining Marek Szwarc’s technique will help my reader grasp all that is sound, and vigorous, and candid in an artist who, instinctively, loathes affected elegances, and in which an art of good taste would be qualified as barbarian only by virtuosos of warped taste.

Szwarc is a hammerer of metal, the only one in Paris who inscribes figures on copper, portraits, nudes, decorative compositions. Other brass or coppersmiths, Lacroix, Jensen, Monod-Herzen, Linossier, Jean Serrières, for example, use copper in order to cast it into vases, pitchers, cups, utensils. But Szwarc bears in mind that he became since his early adolescence a painter and sculptor, which he embodies when he chases and tempers the ductile material.

The métier of an antique simplicity, traditional coppersmiths tools of former times, of those workers who had been such good artists, and whom we admire at the Louvre and at Cluny.

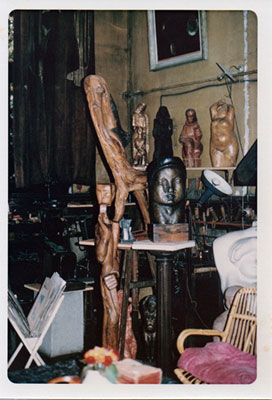

An intricate work space: a vice, points, an iron hammer, a mallet.

But rather listen to the artisan himself as he tells us how he proceeds: “Copper, so malleable to work, transforms itself alternately under the probing tool and the tempering fire. Hammering confers to this rigid material a docile suppleness which permits to imprint the desired forms. The handsome reddish-brown leaf will first be submitted to the steel hammer’s blows that pins down the general lines with the help of the stylus. It is then submitted to the action of the mallet and the iron hammer which smooth out the irregularities. In order to obtain the reliefs, the copper leaf is placed on a wood surface, or sometimes on a lead plaque. At which point the scraper is introduced, imparting to the metal the impression of life. The beauty of the technique is made manifest by the diverse play of the surface planes and shadows. In truth, that’s all.”

To this brief report, let us add this bit of information: before handling his tools, Szwarc draws his preparatory sketches from the model with a few nervous and precise lines on paper.

What the artist, of such humble modesty, does not say a propos this arduous metalwork was succinctly put forward by one of the writers introducing, several years ago, a Parisian exposition of Szwarc and Henri Hertz: “Marek Szwarc has undertaken to save the sculpting of hammered copper … ‘You see,’ he tells me in his atelier which resembles the annex of a smithy or of a tin workshop installed below, from where one hears the bellowing sounds of the forge, ‘it resembles the art of the carver of chased metal, but also a lot to the coppersmith. It’s true, in order to render to this art its liberty and puissance, in the resurrection of a material fallen into servitude, one must have the courage and humility to return to the habits of the Middle-Age and the Renaissance, to be an artisan, to have the skin of the hands encrusted by the brutal caress of the material which one never leaves, with which one lives and searches, side by side.’”

*

Let us now repeat that his inspired themes, the sources from which he draws, are exclusively from the eternal Book.

The soul of this believer is nourished by the poignant or wise legends that the Bible provides him. There is no need to transpose; he beholds. He sees “Jacob wrestling with the angel,” “Moses bearing the tablets of the Law,” the calm “Issachar,” “Eve born from Adam’s rib,” “Ruth asleep alongside Boaz.” And it will be, when the artist’s compositions will assume an ampler decorative importance, “Lot fleeing Sodom,” the admirable “Job and the three friends,” “Abraham’s Sacrifice,” “David and Bathsheba,” “David and Goliath,” “Samson and Delilah.”

The artist is the contemporary of these Hebrews from Genesis and Exodus. When they are reproduced on his copper plaque, he only aims at translating their suffering; the attitudes, the clothing, the décor could be borrowed from today’s humble life and functions solely as an arabesque of lines, planes, and volumes.

And – this is an essential point to observe – Marek Szwarc personifies, although to some extent formed in our country and living in Paris, the very type of the Jewish Polish artisan. An art critic from Poland, Mr. Edward Woroniecki, a student of the origins of Szwarc’s art, after having noted the immediate influences of Polish instruction (the Trade School of Lodz, for example, and brief lessons with the sculptor Mr. Laszczka, who taught some fifteen years at the Art Academy in Krakow), finds in Szwarc a resemblance to the potent realism of the medieval maître Wit Stwosz. “The artist,” Mr. Woroniecki writes, “loves profoundly his fatherland. The idea of transposing the personages under a so-called historic form is completely foreign to him. He fits the biblical scenes in familiar surroundings. They are Jewish Poles from the provinces with their characteristic attire, celebrating Passover or gleaning the ears of corn with Ruth, musicians or apostles, or assisting in the deposition of the body of Christ from the cross. Christianity, in effect, appears to Marek Szwarc to be the natural complement of the Mosaic faith. Such a rather particular mysticism is generous and tolerant. He is never inspired by the narrow fanaticism of the Talmud.”

*

Such are, summarized perhaps too succinctly, Marek Szwarc’s notions. His art, which plunges its roots into the past of the ghettos and in which the moving accent like the ancient songs in the synagogue of Wilna, is a return to popular imagery. And, in as much as this may seem paradoxical, these stern manners, this severe style, of a “common” naïveté, are profoundly in accord with what art of the most modernist sort supplies in our regard; by virtue of its poetic concepts, by its firm and generous execution, by the sense of its cadenced dispositions, by the sharp graphics written in view of the material and which commands this very material, it is apparent that Marek Szwarc is in harmony with the most audacious innovators of our times, who seek him out and see him as a maître.

Will this unique example bring about a renaissance of Jewish art, as is conceived by this austere and gentle artisan? Will we see ateliers of sacred art of Israel comparable to the ateliers of the opulent and erudite Maurice Denis? I do not know, and the first pages of the present essay grant us a glimpse at the response which one might offer to this question. The fact remains that Marek Szwarc has no other ambitions than improving his oeuvre; he is not troubled by cant or proselytism. If he is a precursor, he will be one without having wished it upon himself.

Translation by Gabriel Levin